The processed white foods : are they evil?

If you listen to those advocating high protein diets – from Atkins to Paleolithic, then white bread and white rice are a scourge that has caused modern man obesity, heart disease, diabetes, and a lower lifespan. But countering that comes a study from the January 2015 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

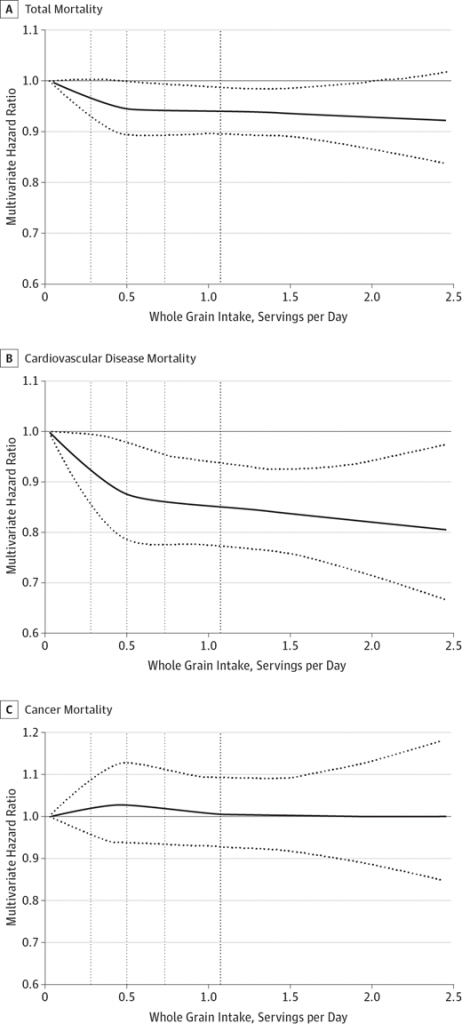

It turns out that dietary whole grain intake reduces the risk of death as well as heart disease and diabetes.

Not just bread- but whole grains in general, and that definition leaves a wide open gap to what we are talking about. I never know what a whole grain is, but they defined what they meant:

Quoting from the study:

Intakes of whole grain were estimated from all grain-containing foods (rice, bread, pasta, and breakfast cereals) according to the dry weight of the whole grain ingredients in each food. Whole grain consumption from breakfast cereal was derived from more than 250 brand name cereals based on information provided by product labels and breakfast cereal manufacturers. In our study, whole grains included intact and pulverized forms that contained the expected proportion of bran, germ, and endosperm for the specific grain types. By definition, the following foods and ingredients were considered whole grains: whole wheat and whole wheat flour, whole oats and whole oat flour, whole cornmeal and whole corn flour, whole rye and whole rye flour, whole barley, bulgur, buckwheat, brown rice and brown rice flour, popcorn, amaranth, and psyllium. In the FFQ, we also asked the frequency of consuming added bran (oat bran and other bran) and added wheat germ. Intakes of bran and germ were derived directly from whole grain foods and those added to foods. Total bran and total germ are the sum of intakes from both sources.

So what is the magic here?

The belief that whole grain is better than processed has its basis is historical, and in this case the primary basis came history.

The magic goes back to the latter half of the eighteenth century, beriberi was widespread throughout Southeast Asia, especially in Japan, as well as China, Indonesia, Java, and the Philippines. A little over one third of all illness in the navy was from beriberi. Beriberi is a disease caused from a deficiency of vitamin B1 (thiamine). Without thiamine, the body cannot utilize the energy from carbohydrates, fat, and protein. Symptoms include weight loss, weakness, pain in the limbs, impaired sensory perception, emotional disturbances, irregular heart rate, and swelling of the lower extremities (edema). It might start with difficulty walking, followed by tingling or loss of sensation, mental confusion, pain, and can progress on to heart problems and death. The confusing complex of symptoms all comes from the deficiency of just one vitamin.

Over the course of several years, a Japanese Navy Surgeon, Takaki Kanehiro looked at various factors as a cause of beriberi—clothing, living quarters, and even the temperature of the places the ships went. He noted that the officers of the ship rarely contracted beriberi, and this became his first clue that the food might be the cause, as the officers had access to more varieties of foods, while lower ranks, and particularly the prisoners on the ships, had more beriberi and tended to eat primarily polished white rice. Takaki also noted that when ships were in port, many of the sailors recovered. His belief that diet was a component of beriberi had to be tested.

His experiment was set up with a training ship that was given increased provisions of bread, meat, and vegetables. The ship followed the route of another ship that had 169 cases of beriberi among the 370-member crew, with twenty-five deaths. In the test run, there were no cases of beriberi. This prompted reforms to increase the food provisions among the Japanese Navy. In 1882, when Takaki had started looking at beriberi there were an average of 404 cases of beriberi for every one thousand sailors, and after his reforms were implemented in 1886 there was less than one case per thousand.When people ate diets of white rice, they developed beriberi, as vitamin B1 had been removed in the processing. That happens to be the “germ” of the rice that contains the vitamins. Strip that part away and the remaining rice has low nutrient value.

This discovery, about how whole rice and earlier studies showing that citrus decreased nutrient deficiencies, led to the widespread belief that we need “whole foods.”

Beriberi was first noted when people started to process rice. The first descriptions are from the Chinese, where the wealthy used rice that was called “polished white rice,” which is where the rice has been processed to remove the husk, the germ, and the bran.

Today white rice is fortified with vitamin B1, as well as other vitamins and essential ingredients. Brown rice today is often contraindicated for increased consumption because of the higher arsenic levels found in brown rice. In today’s world it is safer for people who consume rice to use the white instead of the brown rice. Modern rice is fortified, meaning that a process is used where vitamins and minerals are bound to the rice and are easily bioavailable to the gut to use. Since the fortification of rice, as well as other products, not only have nutrient deficiencies disappeared, but fortified rice is able be stored far longer than brown rice, and has lower levels of the pollutants that have come from modern agriculture.

Processed foods that led to a deficiency of vitamins were responsible for rickets (vitamin D deficiency), pellagra (vitamin B3—niacin deficiency), pernicious anemia (vitamin B12), bleeding disorders (vitamin K), and night blindness (vitamin A), in addition to beriberi. Fortifying foods with these micronutrients led to the reduction of widespread micronutrient disease in countries where processed food was needed to feed the masses. Brown rice, for example, could not be stored or transported without becoming rancid after eight to ten months, whereas polished white rice could be easily stored and transported and kept as a ready energy source for up to ten years—but it needed to be fortified with vitamins.

The advantages of processed foods are portability, stability, and a long storage life. Micronutrients were what chemists in the first half of the twentieth century were trying to isolate in order to supplement food. Chemists worked to isolate the micronutrients and return those nutrients to the processed foods to avoid deficiency.

But the study didn’t look at “fortified” foods, it looked at what it called “whole grain” and as you can see- its idea of whole grain was broad and open. But science has shown us what the deficiencies are that whole grains make up for – besides the micronutrients of vitamins and the fiber, there appears to be no magic in the whole grain that we cannot fortify in bread.

But what about Paleolithic diets? Isn’t it odd- modern man lives longer than the caveman and we eat grains?

Reference:

Association Between Dietary Whole Grain Intake and Risk of Mortality: Two Large Prospective Studies in US Men and Women. JAMA Intern Med. Published online January 05, 2015. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6283. Wu H, Flint AJ, Qi Q, et al.