In reading the press about medical errors one gets the impression that malpractice is being committed left and right in hospitals. But lets look a bit deeper into this and see if we can make some sense out of what the authors are claiming is the third leading cause of death in the United States. The original article in the British Medical Journal is here.

First, there is no doubt medical errors do occur. They can be tragic, deadly, and debilitating. But do 251,454 patients die because of medical errors every year? The assumption that this is a real number (it isn’t) or that the deaths are preventable (many are not).

Where does the figure come from? The review actually comes from three papers published over seven years ago and were based on 35 patients who died that were considered preventable.

35

From this the extrapolations occur. Does that seem off to you. Here are a few examples of what would be considered a medical death:

If a person has severe underlying heart disease, and undergoes a procedure and dies of a heart attack, it would be considered a medical death. Did the procedure cause the death, or put stress on a heart that was already compromised?

When we do surgery we often give patients blood thinners to prevent deep vein thrombosis which can lead to pulmonary embolism and death. There is no 100 per cent way to prevent this complication, but by using blood thinners we reduce it over 1000 fold. Still, every year patients will develop these complications and die. Is that a preventable death? What could be done to prevent that?

My brother, Jimmy, had terminal lung cancer. He elected to have some chemotherapy in an attempt to decrease symptoms. The chemotherapy used was fully approved for his form of cancer. Sadly, he became septic after the chemotherapy decreased his immune system, spent 18 days in the ICU and died. Was that a preventable medical error?

All Adverse Events Are Not Preventable

Wound infections after surgery have been greatly reduced in the last forty years, but it is never going to get to zero. A wound infection could be as complex as life-threatening MRSA with multiple procedures that can lead to the death of the patient.

Patients who go into hospitals are ill, and will have an expected mortality and morbidity. But all adverse events are not a result of medical errors.

How Big Is The Problem

The paper states that they have made generous extrapolations and all based on statistics. But according to the CDC about 715,000 died in hospitals in 2010 and over 3/4 of them were age 65 and older and almost a third of them were over 85 years old. In the United Kingdom forty per cent of the hospital deaths are in patients over 80 years old. We also know that 80% of people will die in a hospital. That does not mean avoiding the hospital will mean you won’t die.

Looking at the statistics it would seem like almost 35% of people who enter the hospital will die. That doesn’t happen.

How Do We Fix It

The American College of Surgeons as well as other major medical societies have major campaigns to reduce medical complications. We all strive for zero errors, but we should not confuse errors in treatment (getting the wrong medicine, wrong-side surgery, over dose of medicine) with adverse outcomes that come with the disease or as a part of the treatment of the disease.

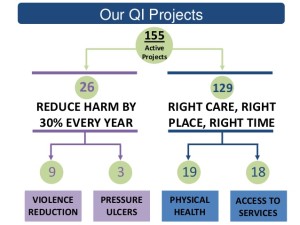

One of my fellow surgeons, Jason Leitch in Scottland his helping reduce errors in that system:

Continuous improvement in patient care is needed. Checklists, like pilots use, help. But unexpected hospital deaths, as opposed to expected hospital deaths are different beasts entirely.

Much like the airplane that crashes, medicine often find underlying causes that physicians did not know about leading to a death that, in retrospect, was not preventable. When an airline crashes evaluation sometimes finds unique circumstances that lead to better quality for further aircraft design and development. A comprehensive review of unexpected deaths is the hallmark of great care.

The British Medical Journal paper, and is conclusions, is sloppy science, and does not provide any help for healthcare in the United States or elsewhere. It does however provide the researchers with long-careers and grants to study statistics and provide trial lawyers with fodder. It also provides “alternative medicine” fans a new statistic to justify their treatments which do not work.